U pendin g a decades-long effort to reduce global trade barriers, China and the United States began mutually escalating tariffs on $450 billion in trade flows in 2018 and 2019. These tariff increases reduced trade between the US and China, but little is known about how trade was affected in the rest of the world.

In The US-China Trade War and Global Reallocations (NBER Working Paper 29562 ), Pablo Fajgelbaum , Pinelopi K. Goldberg , Patrick J. Kennedy , Amit Khandelwal , and Daria Taglioni find that the trade war created trade opportunities for other nations and increased overall global trade by 3 percent. Export growth was stronger, on average, in countries with larger shares of their exports governed by strong trade agreements, and in countries with more foreign direct investment.

While the US and China largely taxed each other and depressed their bilateral trade flows, bystander countries increased their exports to the US and the rest of the world and global trade increased overall.

In 2018 and 2019, the US raised tariffs on imports from China. It also raised tariffs on a subset of products from other countries, mainly in machinery and metals. China retaliated and imposed tariffs on imports from the US. At the same time, it also lowered tariffs on imports from the rest of the world. The tariff increases were a major departure from long-run trends towards tariff liberalization across the globe.

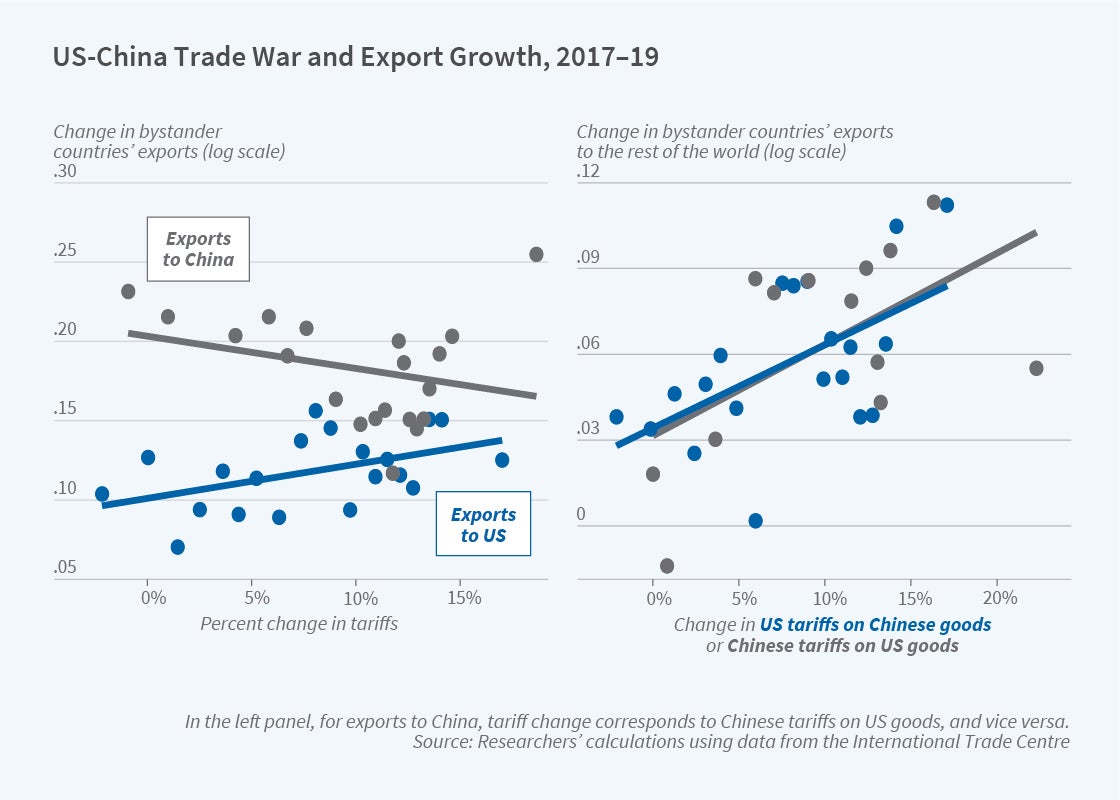

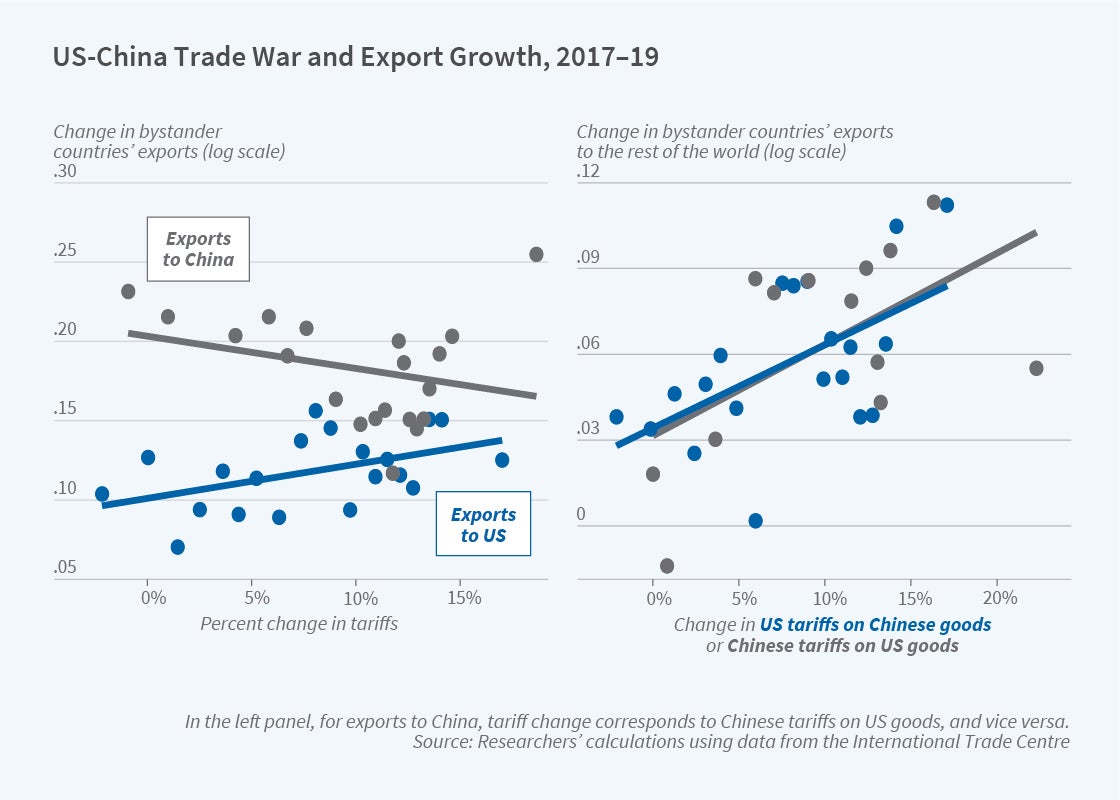

To analyze the impact of these four sets of tariff changes on global trade, the researchers match the tariffs’ movements to global bilateral trade data from the International Trade Centre for the top 50 exporting countries, excluding oil exporters. Their analysis compares the export growth across products that were subject to different tariff increases by the US or China.

The US and China reduced exports of products subject to increased tariffs. US exports to China fell by 26.3 percent while exports to the rest of the world increased modestly, by 2.2 percent. China’s exports to the US declined by 8.5 percent and its exports to the rest of the world rose by a statistically insignificant 5.5 percent. The researchers further find that trade in the products targeted by the tariffs increased among bystander countries. These nations did more than reallocate global trade flows across destinations; their overall exports to the world increased. Because of this response from the rest of the world, on net, they calculate that the trade war raised global trade by 3 percent.

The researchers find that the winners and losers in the trade war are explained primarily by heterogeneity in exporters’ responses to trade-war-induced price changes, rather than by specialization patterns. Many of the countries with strong export growth were operating along downward sloping supply curves and selling products that substituted for those previously supplied by the US or China. The countries that benefited the most were those with a high degree of international integration, as proxied by their participation in trade agreements and foreign direct investment. France, for example, increased its exports both to the US and to the rest of the world in response to the tariffs. Spain increased its exports to the US, but its exports to the rest of the world shrank. In South Africa and the Philippines, the tariff increases reduced both exports to the US and exports to the rest of the world. Statistically significant increases in bystander countries’ exports in response to the tariffs occurred in 19 of the 48 countries in the data sample. One country reported a statistically significant decrease; there were no statistically significant impacts in the remaining 28 countries.