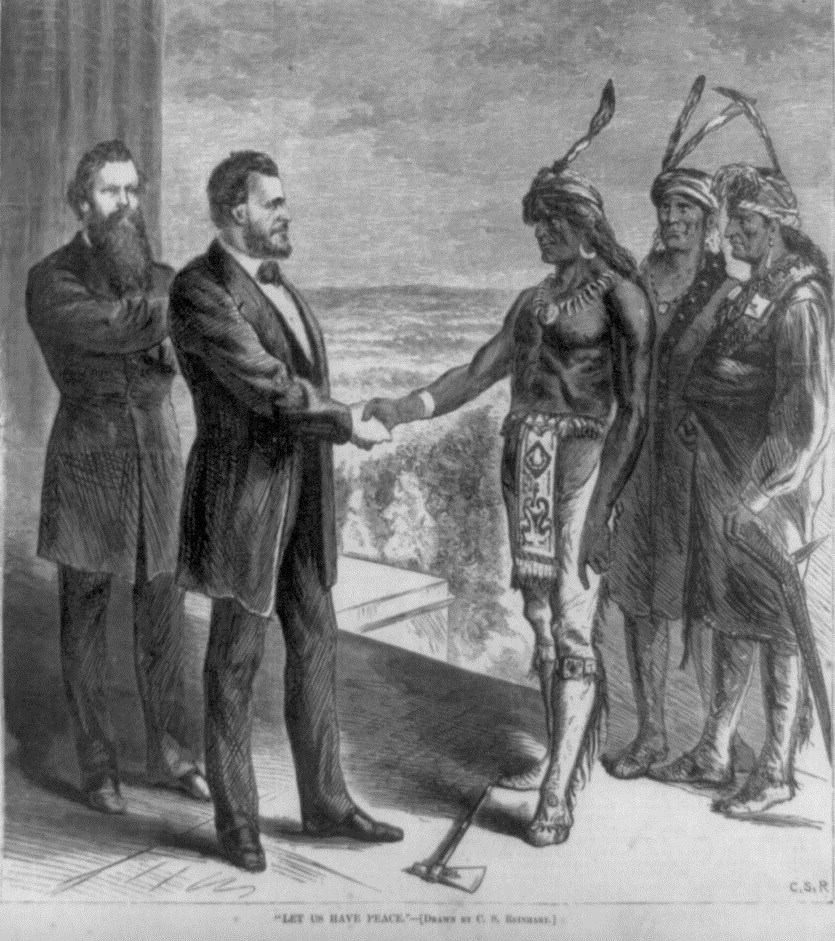

Ulysses S. Grant was sworn in as the 18 th President of the United States on March 4, 1869. At the time of his inauguration, the United States was several years removed from the end of the American Civil War. President Grant, however, was still wrestling with major questions about the country’s future. Some of those questions revolved around the topic of westward expansion. A growing number of settlers were making their way to new states and territories in the West. A vast railroad infrastructure—including the nearly completed Transcontinental Railroad—was expanding by the day. Leaders of various Indian nations demanded that previous treaties with the U.S. government be upheld and that their lands be protected from this onslaught of settlers. Grant tried to juggle multiple desires. On the one hand, he called for reform in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and peaceful relations with Native Americans. On the other hand, he supported continual population growth in the West through settler migration and territorial expansion.

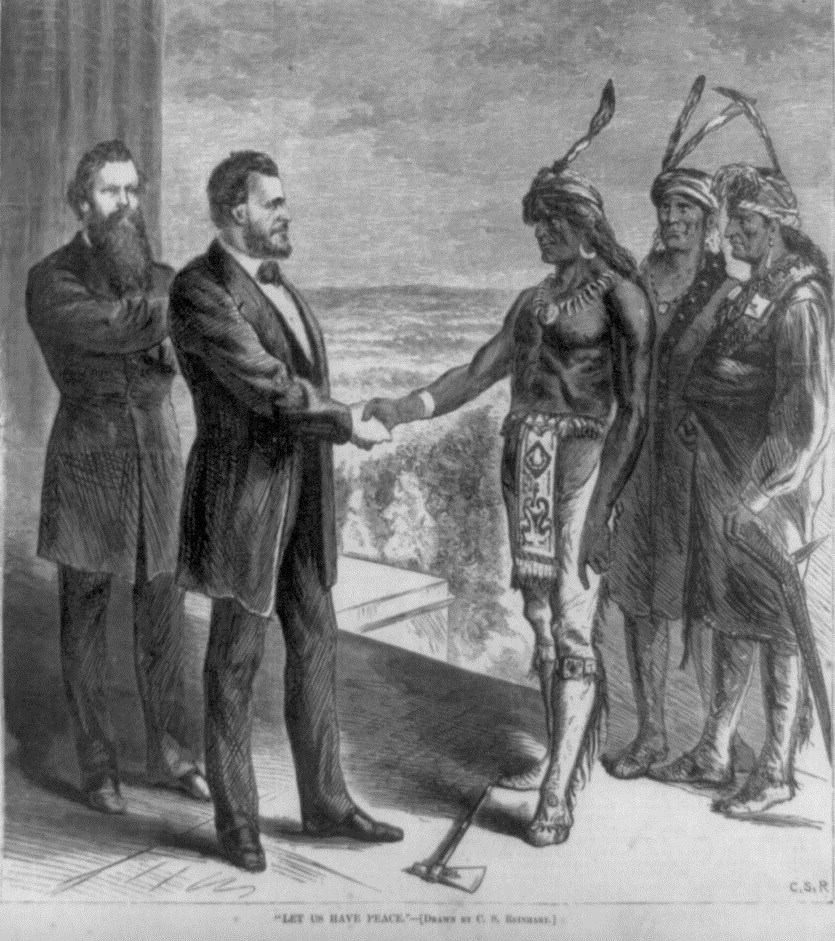

Grant had limited interactions with Indians during his time in the U.S. Army prior to the Civil War. He noted during the Mexican-American War that many Mexican residents were of Indian ancestry. While stationed at Columbia Barracks in Washington Territory in 1853, Grant wrote to his wife Julia that “[Indians] about here are the most harmless people you ever saw. It is really my [opinion] that the whole race would be harmless and peaceable if they were not put upon by the whites.” Grant also befriended Ely S. Parker (whose tribal name was Hasanoanda, later Donehogawa), a Seneca Indian who was working as an engineer for the U.S. Treasury in Galena, Illinois, while the Grant family lived there in 1860. During the Civil War, Parker served on Grant’s staff and assisted with drafting the surrender documents Confederate General Robert E. Lee signed at Appomattox Court House. In fact, the surrender documents are written in Parker’s handwriting.

Towards the end of the Civil War, Congress established the Doolittle Commission to investigate “the present condition of the Indian tribes, especially into the manner in which they are treated by the civil and military authorities of the United States… and examine fully the conduct of Indian agents and superintendents.” The Commission found that there was rampant fraud and corruption in the BIA. In the Plains, a group of Lakota, Arapahoe, and Northern Cheyenne under Red Cloud regularly attacked wagon trains and settlers making their way through lands in present-day Montana and Wyoming. The Bozeman Trail was a particularly noteworthy target since that trail ran through land that were guaranteed to these tribes through the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie. Seeking peace and reform, Congress established the United States Indian Peace Commission in 1867.

Ely Parker (Donehogawa), a Seneca, served as a member of the Peace Commission and created a four-point plan for establishing long-term peace with these Plains tribes. Grant fully endorsed Parker’s recommendations. In his plan, Parker sought to transfer Indian affairs from the BIA to the War Department, establish a permanent land guarantee to the various Indian tribes, provide more oversite of all Indian agencies managed by the federal government, and create a permanent commission composed of both Indians and whites to assist the president with formulating fair policies for both groups. As Grant stated to William T. Sherman, he wished that these policies would help “to deal farely [sic] with the Indians and protect them from encroachments by the Whites.” A revised Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868 ended the Red Cloud War by promising to close forts along the Bozeman Trail and to grant hunting rights outside the boundaries of the Great Sioux reservation.

Historian Philip Weeks argues that popular thinking about Indians among white Americans in the nineteenth century split into two distinct camps. “Assimilationists” believed that Indians could be “civilized” as they learned the ways of mainstream white society, including farming, Christianization, the English language, concepts such as democracy and private property, and eventually U.S. citizenship. “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” was a common refrain heard among assimilationists. Conversely, “exterminationists” believed that Indians could not assimilate and that efforts to “civilize” them were futile. As such, they supported the idea of removing Indians to distant reservations far removed from white settlers, even at the expense of their lands and in some cases their lives. Assimilationists also supported the reservation system, but argued that this system was the best at temporarily protecting Indians from white settlers until they were prepared for U.S. citizenship.

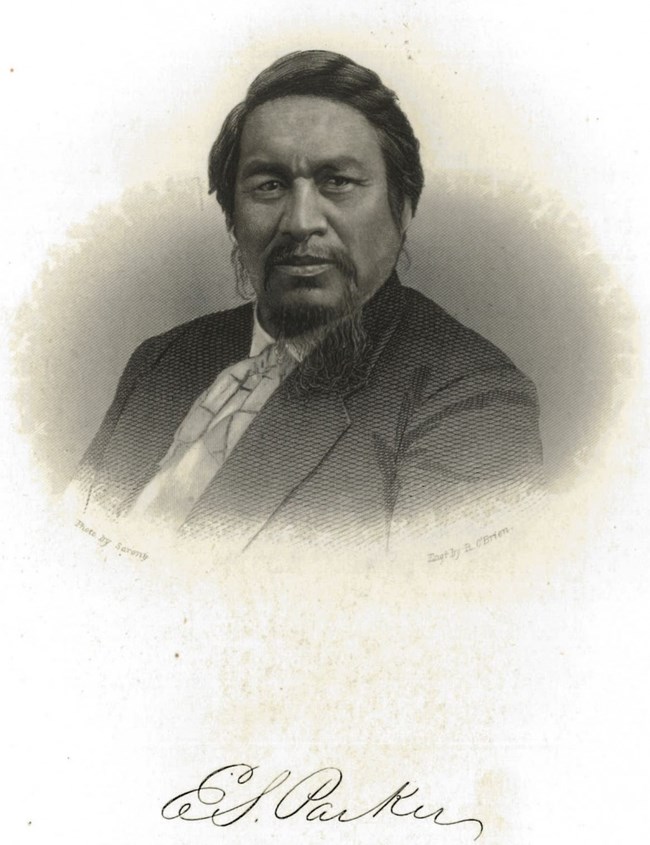

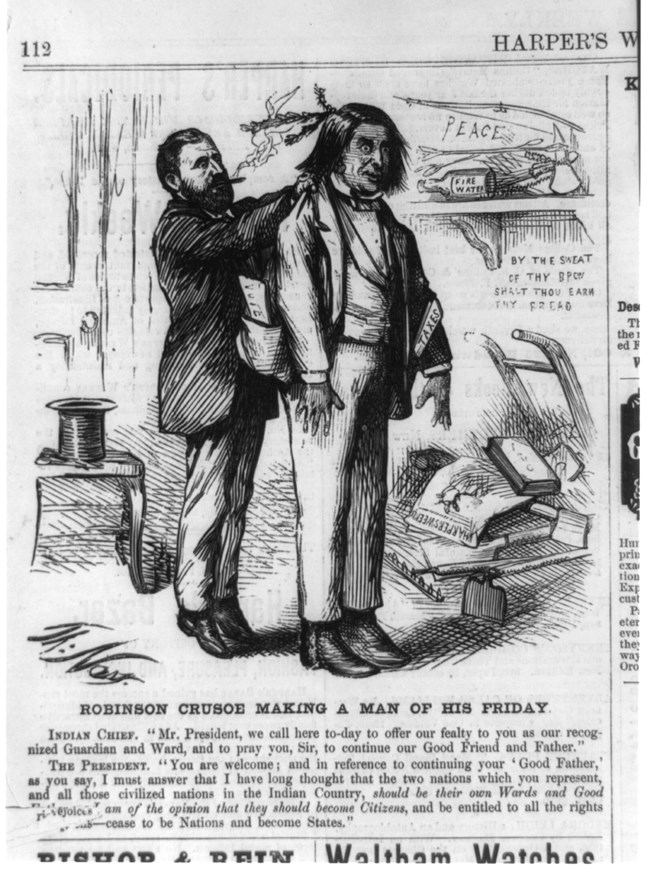

President Grant embraced assimilationist views for the most part. He announced in his First Inaugural Address that “the proper treatment of the original occupants of the land, the Indian, is one deserving of careful study. I will favor any course towards them which tends to their civilization, Christianization and ultimate citizenship.” Later in 1869 he announced that “from the foundation of the Government to the present the management of the original inhabitants of this Continent, the Indian, has been one of embarrassment, and expense, and has been attended with continuous robberies, murders, and wars.” To address these issues, Grant appointed Parker as head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and helped establish a Board of Indian Commissioners to oversee the BIA. Some Indian tribes supported Grant’s efforts at peace. For example, a delegation of Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw leaders praised Grant at the beginning of his presidency. The Quaker Society of Friends expressed their desire to assist President Grant and offered to send missionaries to help manage reservations and Christianize Indians. All seemed to be going according to plan.

drawing of President Grant standing behind a Native American man and helping him put on a suit." width="" />

drawing of President Grant standing behind a Native American man and helping him put on a suit." width="" />

Political reforms often create unintended consequences, both negative and positive. Grant soon learned this lesson the hard way. He believed that transferring Indian Affairs to the War Department would cut out greedy officials who were often appointed to government positions because of their connections and not because of their talents. Military officials would not be tempted by bribes or government patronage. Moreover, “if the men who have to do the fighting could have the management in time of peace [they] would be most likely of any people to preserve peace, for their own comfort if for no other reason,” Grant argued. Congress, however, resented this effort to cut into their patronage and passed a law in 1870 banning military officers from serving at trading posts or Indian reservations. This law inspired President Grant’s “Peace Policy” of distributing the management of Indian reservations to various Christian denominations, including Catholics, Methodists, Baptists, and Quakers. Additionally, the Board of Indian Commissioners resented Ely Parker’s authority in the BIA and undertook a campaign to remove him from office. Feeling that his authority had been undermined, Parker resigned from office in 1871.

Grant also discovered that not every Indian nation was ready to embrace the changes his administration proposed. Some Indians had no interest in moving to reservations, farming, Christianity, or becoming U.S. citizens. For tribes who refused to abide by the “Peace Policy,” a different plan that might be described as “Peace by Force” was developed. As violence between Indians and settlers increased, Grant described this plan in an 1872 letter to General John Schofield: “Indians who will not put themselves under the restraints required will have to be forced, even to the extent of making war upon them, to submit to measures that will insure [sic] security to the white settlers of the Territories,” he argued.

Some of the worst cases of violence and bloodshed between the U.S. military and Indians took place during Grant’s presidency. For example, The Camp Grant and Marias Massacres were two incidents in which mostly women and children were killed by U.S. Army troops. A historic rivalry between the Modoc and Klamath in the Pacific Northwest was further exacerbated when the Modoc were moved to the Klamath reservation in Oregon. When the Modoc tried to return to their traditional lands at Tule Lake, a bloody conflict called the Modoc War broke out. The Ponca tribe maintained a reservation in northeastern Nebraska along the Missouri River. After a years-long dispute with neighboring tribes in Dakota territory, the Ponca endured their own Trail of Tears as they were forced to relocate to Oklahoma in 1877.

The Grant administration also engaged in questionable practices to acquire the Black Hills, located in present-day South Dakota. This land had been guaranteed to the Lakota, Dakota, and Arapaho nations in perpetuity through the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. General George Armstrong Custer led an expedition of the Black Hills in 1874 with the goal of establishing a military fort, finding possible travel routes through the area, and possibly finding gold. This expedition was in violation of the Treaty of Fort Laramie. When Custer’s forces discovered gold, newspapers around the country reported the news. Struggling to contain the rush of white speculators illegally entering the area for gold, the Grant administration tried to purchase the Black Hills. When the tribes refused to sell, President Grant called a meeting on November 3, 1875 to devise a strategy to take the Black Hills. Soon after this meeting, the U.S. Army stopped all efforts to prevent miners and speculators from entering the area. These growing tensions set the conditions for the Battle of Little Bighorn (also referred to as the Battle of Greasy Grass) on June 25-26, 1876, in which Custer and 267 other troops in his force were killed by Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho forces under the command of Crazy Horse, Chief Gall, and other Indian leaders. While the battle was a victory for the tribes, the U.S. Army returned to the Plains with larger numbers. In October 1876, more than 200 chiefs and headmen of the various tribes were forced to sign a new agreement ceding the Black Hills to the U.S. government.

Historians have offered differing interpretations of Grant's policies. Some Grant biographers such as William McFeely, Jean Edward Smith, and Ron Chernow argue that Grant’s policies were well intentioned. They argue that Grant rejected the wholesale extermination of Indians that was advocated by other generals, such as William T. Sherman and Philip Sheridan, and much of the public. Conversely, other scholars such as Weeks and Mary Stockwell suggest that Grant’s assimilationist polices were rooted in destroying Native American culture and lifeways in the interest of fulfilling Manifest Destiny. “Never once in all his planning did President Grant wonder whether the Indians agreed with him, nor did he ever consider how unhappy they might be contemplating the future he had laid out to them,” Stockwell argues. Finally, Indigenous scholar Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz argues that “many of the intensive genocidal campaigns against Indigenous civilians [in the nineteenth century] took place during the administration of President Grant.” Regardless of President Grant's intentions, what cannot be denied is that Indiegnous Tribes endured incredible tragedy during his presidency, including forced removal to reservations, the destruction of their lifeways and cultures, and horrible violence at the hands of the U.S. government.

These complex stories of military conflict, harsh violence, and Indian removal play an important role for understanding how federal Indian policy reflected the desires of a country eager to expand its control westward during the Reconstruction Era.

Ned Blackhawk. Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empire in the Early American West. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa. Crooked Paths to Allotment: The Fight Over Federal Indian Policy After the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Alexandra E. Stern. “Reconstructing Approaches to America’s Indian Problem: Indian Policy in the Late Nineteenth Century.” U.S. History Scene.

Mary Stockwell. Interrupted Odyssey: Ulysses S. Grant and the American Indians. Carbondale. Southern Illinois University Press, 2018.

Philip Weeks. “Farewell, My Nation: American Indians and the United States in the Nineteenth Century. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons (3rd Edition), 2016.